Organizations spent $359 billion globally on training in 2016, but was it worth it?

Not when you consider the following:

- 75% of 1,500 managers surveyed from across 50 organizations were dissatisfied with their company’s Learning & Development (L&D) function;

- 70% of employees report that they don’t have mastery of the skills needed to do their jobs;

- Only 12% of employees apply new skills learned in L&D programs to their jobs; and

- Only 25% of respondents to a recent McKinsey survey believe that training measurably improved performance.

Not only is the majority of training in today’s companies ineffective, but the purpose, timing, and content of training is flawed.

Learning for the Wrong Reasons

Bryan Caplan, professor of economics at George Mason University, and author of The Case Against Education, says in his book that education often isn’t so much about learning useful job skills, but about people showing off, or “signaling.”

Today’s employees often signal through continuous professional education (CPE) credits so that they can make a case for a promotion. L&D staff also signal their worth by meeting flawed KPIs, such as the total CPE credits employees earn, rather than focusing on the business impact created. The former is easier to measure, but flawed incentives beget flawed outcomes, such as the following:

We’re learning at the wrong time. People learn best when they have to learn. Applying what’s learned to real-world situations strengthens one’s focus and determination to learn. And while psychologist Edwin Locke showed the impact of short feedback loops back in 1968 with his theory of motivation, it’s still not widely practiced when it comes to corporate training. Today’s employees often learn uniform topics, on L&D’s schedule, and at a time when it bears little immediate relevance to their role — and their learning suffers as a result.

We’re learning the wrong things. Want to see eyes glaze over quicker than you can finish this sentence? Mandate that busy employees attend a training session on “business writing skills”, or “conflict resolution”, or some other such course with little alignment to their needs.

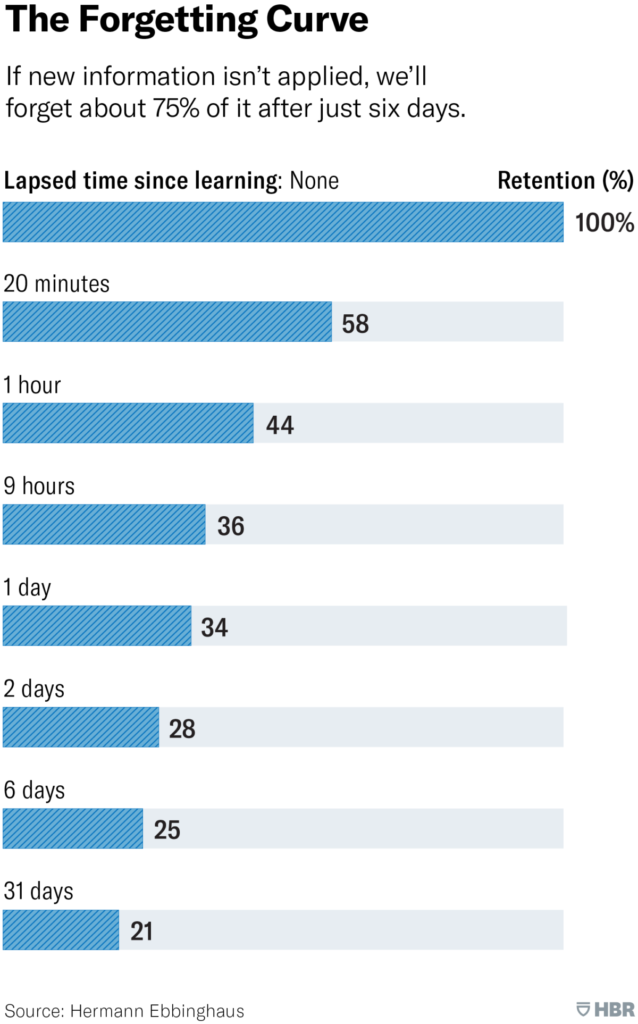

We quickly forget what we’ve learned. Like first year college students who forget 60% of what they learn in high school, studying merely to get the CPE credit suggests that employees, too, will quickly forget what they learn. German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus pioneered experimental studies of memory in the late 19th Century, culminating with his discovery of “The Forgetting Curve.” He found that if new information isn’t applied, we’ll forget about 75% of it after just six days.

Use It or Lose It

We can blame biology — and our innate, evolutionary desire for survival — for the fact that humans quickly forget what we learn. As Matthieu Boisgontier, of the University of British Columbia’s brain behavior lab put it, “Conserving energy has been essential for humans’ survival, as it allowed us to be more efficient in searching for food and shelter, competing for sexual partners, and avoiding predators.” As a result, our brains quickly forget what we don’t use. Incorporating new learning into your work is one way to retain knowledge. Another is spaced repetition. Originally proposed by psychologist Cecil Alec Mace in 1932, it refers to spreading learning out over time (material should be reviewed in gradually increasing intervals of roughly one day, two days, four days, eight days, and so on). This approach takes advantage of the psychological spacing effect, which demonstrates a strong link between the periodic exposure to information and retention. Studies show that by using spaced repetition, we can remember about 80% of what we learn after 60 days — a significant improvement.

Sadly, most L&D programs overlook these biological realities and invest billions of dollars into what amounts to transfers of quickly forgotten information.

What needs to change

Today’s fast-moving business landscape calls for organizations and their people to adapt to changing circumstances rapidly, and to always be learning. As Wired co-founder Kevin Kelly puts it, “Get good at beginner mode, asking dumb questions, making stupid mistakes, and teaching others what you learn.”

Lean learning, which pays homage to Toyota’s lean manufacturing system, stresses using effort only when it’s needed, improving outcomes, and cutting waste; it’s short, affordable, and provides employees and organizations with an immediate capability update.

Lean learning is about:

- Learning the core of what you need to learn

- Applying it to real-world situations immediately

- Receiving immediate feedback and refining your understanding

- Repeating the cycle

Like lean manufacturing and the lean startup before it, lean learning supports the adaptability that gives organizations a competitive advantage in today’s market.

How to Apply Lean Learning

Think 80/20. Tim Ferriss, entrepreneur and author of The Four Hour book series, is an advocate of a lean learning method he calls DiSSSCaFE. He suggests identifying the minimum learnable unit (MLU), and applying the Pareto Principle. If you want to learn Japanese, focus on the 20% of words and phrases that show up 80% of the time. Then apply what you learn in actual conversations with Japanese speakers as frequently as needed.

Apply learning to real-world situations. At Collective Campus, we don’t just teach executives a specific innovation methodology. We first ensure that they can actually apply the methodology internally, and we request that they bring real-world projects to workshops so that we can apply what’s learned in real-time, shorten the feedback loop, deliver business outcomes, and encourage “aha” moments.

Leverage guided learning. Rather than provide training at specific intervals, guided learning embeds continuous learning into a live application. Think screen pop-ups as-you-go that support rapid, context-sensitive, and personalized learning. This is especially applicable for functional leads, employee on-boarding, cross functional teams, IT, and end-user training.

Personalize content. Using today’s technologies, you can personalize training so that it adapts lessons based on employee performance, tailoring content to every single employee’s needs, learning style, and delivery method.

Provide ongoing support. Providing employees with further support after a learning session via a combination of instant messaging, voice messaging, and chatbots ensures that they can apply learning to specific challenges.

Activate peer learning. When your employees want to learn a new skill, they typically don’t Google it or refer to your learning management system (LMS) first; 55% of them ask a colleague. When you account for the fact that humans tend to learn as they teach, peer learning offers a way to support rapid, just-in-time learning, while strengthening the existing understanding your employees have about concepts. It could be as simple as establishing an online marketplace, or periodic peer learning workshops, to connect employees who are willing to teach specific skills with colleagues who want to acquire such skills. Incentivizing peer learning by incorporating it into performance reviews can ensure that employees continue to invest time into the program.

Offer micro courses. Give employees short, bite-sized learning opportunities, which can take the form of digestible, hour-long courses on topics of relevance to an employee’s immediate challenges or opportunities.

Moving From Credits to Outcomes

In order to begin practicing lean learning, organizations need to move from measuring CPEs earned to measuring business outcomes created. Lean learning ensures that employees not only learn the right thing, at the right time, and for the right reasons, but also that they retain what they learn.

And as Eric Ries, author of The Lean Startup, says, “The only way to win is to learn faster than anyone else.” This has never been truer than it is today.

Credit: HBR